Winston Peters, the victim.

Winston Peters needs you to know that he's a victim. He's a victim. And his dog is a victim. His house is a victim. What he has been through is worse than anything anyone else has ever been through. Were there a Victim Olympics, he'd win gold, silver, and bronze.

For two years, men, women and children have been slaughtered in Gaza. The death toll could be anything from 200,000 to over half a million. You might think that watching your husband be shot in the street while trying to get you and your newborn baby food is bad. But have you considered what it's like to have someone break your window?

Dogs.

Nicola Willis says we're all dogs. Chloe Swarbrick's dogs to be specific. And it's important that New Zealanders call anyone who protests against genocide a dog. That's not divisive. That's not encouraging hate.

Am I devastated that someone broke Winston Peters' window? Yeah. But mainly because this will now be used to push through the Summary Offences (Demonstrations Near Residential Premises) Amendment Bill which will impact freedom of speech and protest in this country.

When we see 90 year-old Holocaust survivors being arrested in the UK for holding up signs saying they support Palestine - know that's on its way here because of that bill.

But am I going to dunk on whoever broke the window? No. Because it feels insane to live in Aotearoa right now while our government ignores a genocide. It feels insane that people care more about Winston Peters' window than human lives.

Should we not feel crazy? Should we not feel like nothing we do matters? If you've protested every weekend for two years and had the government steadfastly ignore you - why would you not protest outside the house of the only person who can represent you when it comes to genocide?

In our name, he's supporting a genocidal regime. In our name, he's trying to make protesting genocide unlawful. In our name, he's refusing to say Palestinians exist, that Palestine exists. In our name, he's waiting for Palestinians to be wiped out so he can say he said some strong words about peace.

I know why people feel crazy enough to break a window.

Seeing a baby blown apart once should make you feel crazy. Seeing hundreds of babies blown apart? Seeing people beg for their lives on instagram? Seeing people starving in front of our eyes? Yeah. This isn't normal.

This government wants you to think it's all normal. That we just need to sit back and shut up. That we don't need to ever protest their position. And if we do, our protests must be quiet. Not disturb. Not bother anyone.

They want you to ignore the political violence they encourage. Winston Peters wants you to forget the witch hunt he orchestrated against Hana-Rawhiti Maipi-Clarke who is six decades younger than him, and Benjamin Doyle whose own child was terrified for their life afterward.

David Seymour wants you to ignore his months long campaign against ordinary citizens of Aotearoa whose photos he posted on his Facebook page because they disagreed with him. Or saying he wishes someone would blow up the Ministry of Pacific Peoples.

They want you to ignore the stories they feed to right wing blogs and far-right radio stations about people who are causing them trouble. Because that's not political violence to them.

It's not violent to take away support for teenagers, take thousands of jobs from hard-working people and let them slide into poverty, literally steal school lunches from kids...You bottom feeders, you bots, living in a negative, wet, whiny, inward‑looking country, you retards, you communist, fascist and anti-democratic losers.

They want you to ignore all that.

No.

I will not ignore it. And if that makes me a dog, so be it.

Fuckin' woof.

The real story isn’t Winston Peters’ window no matter how much he wants it to be.

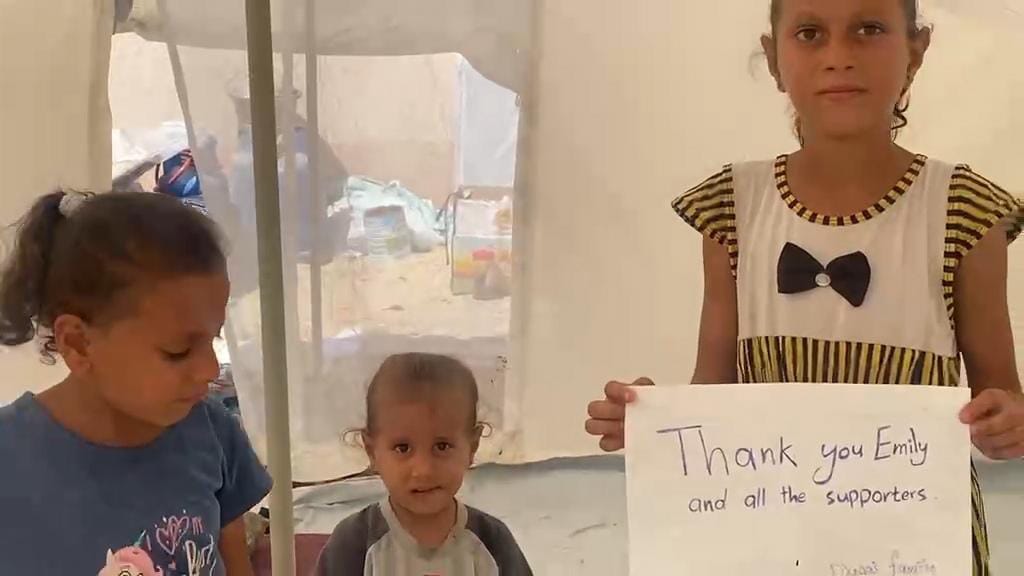

Here's the real story by Dr Jehad Malaka from Palestine as part of the Palestinian Journalism Project I'm running here on Emily Writes Weekly.

Five Times of Displacement After Two Years of Genocidal War

By Dr. Jehad Malaka - If you'd like to share this post without my commentary above - please do. You can read it here as well: www.emilywrites.co.nz/displacement/

The word “refugee” has always been painful since the Palestinian Nakba of 1948. Yet, we have now been given a new label: “displaced.” A word so heavy on the heart that it crushes one’s desire to live.

Gazans treat the term “displaced” as a bleeding scar on their souls, people who once had warm, loving homes, full of life and goodness, now marked by displacement after losing everything: their houses, possessions, and livelihoods.

The machinery of destruction left nothing untouched.

My personal journey of displacement began just one week after the cursed October 7, 2023. I left my large home in Gaza City and moved to an area called Khirbet al-‘Adas, located in the far southeast of Rafah in southern Gaza. I stayed there for seven months, before being forced to flee again, to Khan Younis, after Rafah was occupied, where I remained another seven months.

I then returned to my home after the first Trump Deal, staying for only 40 days before being displaced once more to central Gaza City after the ceasefire collapsed.

A month ago, when the Israeli army began its invasion of the city, I was displaced yet again, this time southward, to Deir al-Balah.

What’s happening now in the South is a continuation of what occurred in Gaza City. The occupation controls more than 70% of the city’s area and has driven people southward, by force and coercion, into open-air camps that lack even the most basic necessities of life.

What does it mean to reach the south after being forcibly uprooted from Gaza? That’s the question that haunts you throughout the endless road, a journey that used to take fifteen minutes in normal times, now stretched to several exhausting hours.

Here, what awaits you is less than a tent and more than despair.

Around you stretches a surreal painting of misery, everything stands still. Men hammer the dry earth, driving the stakes of their tents into it; women wander anxiously, surveying the strange new terrain, fearful of the night that will soon descend upon them in the open air. Some sit in dark corners, silently weeping their grief and immeasurable loss.

A thick darkness blankets the camps. A heavy, unsettling stillness dominates, broken only by faint murmurs, whispers of fatigue, fragments of personal stories, or sudden outbursts of pain that shatter the silence like trapped screams gasping for release.

These tents are not temporary shelters; they are open wounds on the body of this exhausted land. Thousands of them stretch endlessly, forming a web of anguish that mirrors the reality of siege, hunger, and fear. No electricity, no clean water, no healthcare. The heat of the day burns the skin; the cold of the night bites into children’s bones. In the background, explosions echo relentlessly, while drones hover day and night, shadowing every movement like specters of death that know no mercy.

The first night in a tent feels like the first night in prison for an innocent man sentenced to life without having committed a crime. Tears and memories overwhelm you, threatening to break your heart apart. You lie there, staring at the ceiling, your only companion, confiding in it the story of your displacement, the journey from a house to a tent. It’s as if your previous life was carried in the womb of a cloud that miscarried too soon, scattering its fragments across the sky, leaving behind a growing embryo of sorrow that devours past, present, and future alike.

Life in a tent is not a temporary condition; it is like living on a barrel of gunpowder. The unbearable heat, suffocating closeness, and total lack of privacy make daily life an accumulation of physical and psychological pressure. These fragile fabric walls absorb every form of suffering, swelling with silent rage, grief, and betrayal, each tent a ticking bomb waiting to explode, not literally, but emotionally and spiritually.

Inside a tent, there is no tomorrow. You are utterly exposed to the elements and to time itself. Whatever you write to describe the beginning fades away as you drive the sharp stakes of your tent deeper into your own heart. At dawn, you busy yourself with every imaginable form of hardship, healing sorrow with memories, and you whisper to the air: “Do you remember when we had a home?”

Bombing is not the only thing destroying lives here, economic exploitation gnaws at what remains. The social fabric is unraveling; the displaced have become prey to opportunists and landlords demanding outrageous sums for temporary shelter, while most people can barely afford food. Over 90% of those in these camps live in poverty and unemployment, surviving on aid that neither nourishes nor sustains.

This exploitation is not coincidental; it is part of a deliberate system of internal destruction. The occupation seeks to dismantle Palestinian society from within, fragmenting people into isolated individuals competing for crumbs, desperate for shelter even at one another’s expense.

Beneath this deceptive calm lies a deep, unending oppression, with no visible end in sight. The suffering here feels eternal, as though it were a fate written upon these people—inescapable and relentless. Life is cloaked in a terrifying blackness, like graves without light. The sense of hopelessness is suffocating, broken only by the faint glow of small lanterns, silent companions to those living in the darkness.

Yet, despite it all, the candles of hope refuse to go out.

Here, resilience is not expressed through slogans, but through patience and the determination to exist. Some have grown weary of the word “steadfastness,” feeling it unfair to demand endurance beyond human limits. But the very act of living, of surviving, in the heart of death is itself a form of resistance that cannot be denied.

In southern Gaza, particularly in the Al-Mawasi area, which now shelters hundreds of thousands of displaced people driven from their homes by Israel’s war machine, we remain steadfast in our right to life, dignity, and return. The occupation can kill, displace, and destroy, but it cannot erase memory or bury the truth.

In the heart of this darkness, voices of joy still rise, fragile but defiant. Even here, people search for fragments of hope and reminders of their humanity. Just yesterday, a baby girl was born in our camp, and we celebrated her arrival with songs and ululations that echoed into the early hours of dawn.

We know that what is happening today is not merely a humanitarian catastrophe, but a systematic genocide unfolding before the eyes of the world, while silence prevails. Yet we, the people living in tents, understand one thing with absolute certainty: however deep this darkness becomes, it will never extinguish the light of life within us.

.